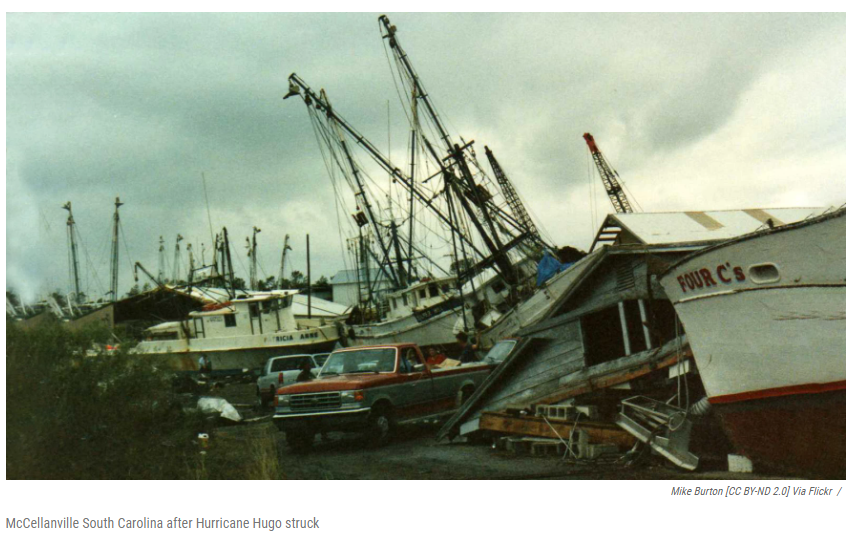

The night I survived Hurricane Hugo in 1989

By Terry Ward – Today is the 33rd anniversary of Hurricane Hugo. I wrote this article for the Greenwood, SC Index-Journal in 1993, on the five-year anniversary of that devastating storm – In September 1989, I was a reporter for the Florence Morning News. Florence, just 60 miles from South Carolina’s Grand Strand, has always been included in the warnings of the ill effects of a hurricane hitting the state’s coast.

September 21-22, 1989 was no exception.

The night of the 21st, a Thursday, I left the newspaper building around 10:30. Before leaving, I along with other members of the newspaper’s staff gathered around a small black and white televisíon set in the editor’s office and listened to a report that Hurricane Hugo would certainly slam into South Carolina’s coast, around midnight.

Outside, as I walked to my car, I noticed the wind was blowing pretty hard and the rain was steady.

I lived, then, in a mobile home about a mile from Francis Marion University.

When I got home the sense of excitement grew as I watched a report on CNN from Wilson High School, just five miles from my home. The school, which had been pressed into service as a hurricane shelter for beach refugees and area residents, was filling up.

Even though Florence had been warned about so many hurricanes throughout the years – it was difficult to remember their names – there was a sense that this one would be different.

A little after 11, my girlfriend and now wife, Lana, who was a student at Francis Marion and lived a mile from me, knocked on my door. Looking at her face I could tell what was exciting for

me, was anxiety for her.

“Come on, we need to get out of here,” she told me in a way, sure that I’d agree. It’s hard to believe, but looking back on it I actually thought I had the option of staying home or seeking shelter elsewhere that night. Lana cleared that up.

At her direction I grabbed what I deemed necessary for the night and we set out for Francis Marion, which had been opened as a shelter. In the yard of the college the trees weren’t just swaying from the wind, they were in a continual bow. On the way into the school’s student center I heard a few defiant (male) students (freshmen no doubt) nobly telling (female) classmates, “We’re going to ride it out.” The defiant ones then darted into a stinging rain, back to the campus dorms.

In the student center, which was half-full with refugees, Lana and I found a clear spot on the floor and spread out a couple of quilts. We sat down and tried to get comfortable.

We had been in the student center for about 30 minutes when one of the six or so inch-thick, safety glass windows on the east side of the building succumbed to the pressure of the 100-plus mile per hour winds. The window, with a loud pop, flew from its frame,

shattering on the floor.

At that point campus security began rounding up those of us in the student center to herd us into the school’s gymnasium, which adjoined the student center and had fewer windows.

While lined up, moving into the gym, over my shoulder I saw the two young men who were “going to ride it out,” dashing, with much more fervor than when they left, back to the student center.

In the gym, we could hear the muffled sounds of the other plate glass windows in the student center popping, one by one, from their frames.

Yes, this hurricane was a little different from the ones in the past.

We stayed in the gym for an hour or more, until a turbine on top of the gym was ripped off by the wind. With the sound of water pouring onto the gym door, we rolled up our quilts again as we were moved into the handball courts.

Although many people in the shelter had radios, there weren’t any stations in the area operating. The lack of communication with the outside, coupled with the eerie yellow low of the emergency lights in the handball court compartments, made the rumors being passed through the crowd all the more believable.

I heard the mayor, and some other people, in Charleston were hiding in the basement of city hall and all of them drowned when the building was washed away. was one of the reports we

heard.

The feeling was surreal as the night passed, and the rumors flowed. There was time to listen to them too, because very few of the refugees slept that night.

It all came to an end around 7 a.m. when one of the campus security guards came in to tell everyone we could go outside. What we saw that morning made you realize how quickly man’s imprint on the planet could be erased or at least covered.

Trees were strewn everywhere. The road we had used to get to the college was not even visible for the trees, much less passable.

Houses and other structures were minus their fronts or roofs and many had large holes in them. Airplanes were toppled and traffic lights hung by a single wire in some places and were non-existent in other areas. The stores were dark with no electricity and trailer parks looked like salvage yards. Mobile homes were blown off their foundations and some had trees splitting them in two.

Maybe it was because everyone was glad to be alive, or maybe the storm served as a kind of equalizer for mankind, but on that bright, sunny morning and for the week following Hugo’s encroachment, Florence had a holiday feeling.

There were reports of neighbors who hadn’t talked before helping each other. There were countless relief caravans from all over the country. The spirit of unity was strong.

Looking back on it, something about that disaster wasn’t all bad.